We were approached a few days ago by Tom Woolmore, the great grandson of one of the group of young men who formed Fylde Rugby Club in 1919 at the Ansdell Institute. He alerted us to the story of Bertie Rothwell, his fate in the WW1 mud of Passchendaele, his subsequent post-traumatic stress disorder, his working career back in St Annes and his love of rugby. This is a touching description of a typical life of a soldier during this horrific conflict. He survived, somehow, although so many of his comrades didn’t. But he had to live with the consequences.

There couldn’t be a better way to mark the Remembrance ceremonies in 2022 than to highlight the contribution of men like Bertie, and women too, to whom we should be so grateful. As we acknowledge Remembrance Day here during the minute’s silence ahead of this game, give a thought to Bertie and the millions of others caught up in armed conflicts then and now. LEST WE FORGET.

{Tom Woolmore and his mother Sue are guest of the Club on Saturday.]

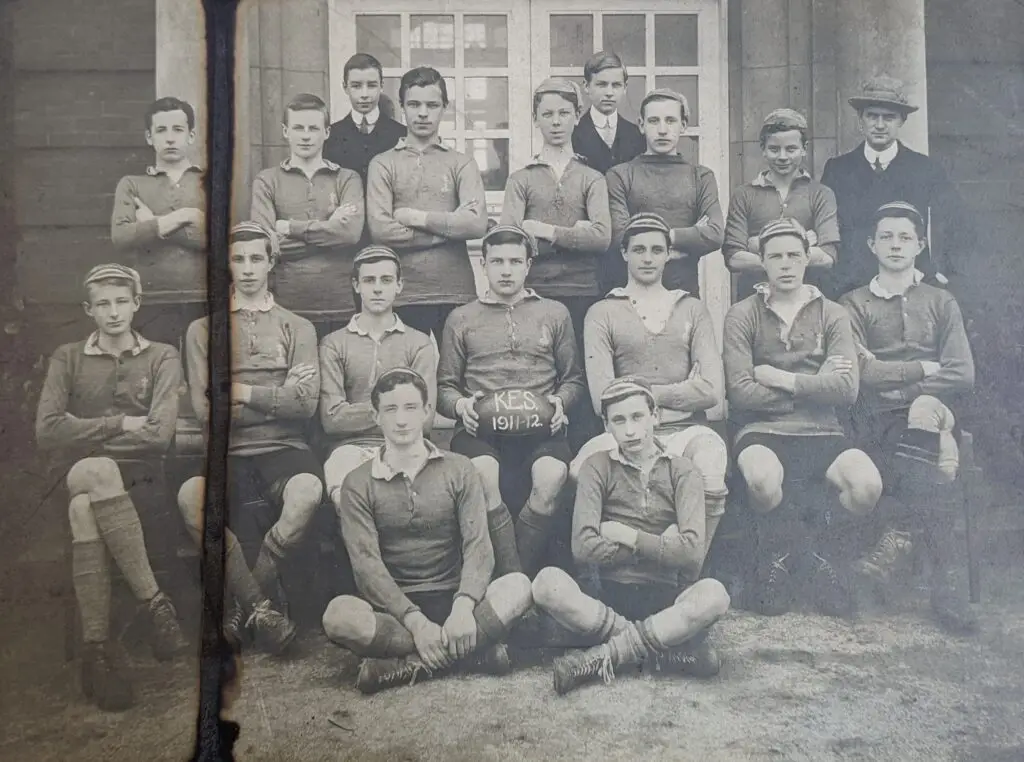

Bertie was born on 9 November 1896 in St Anne’s, Lancashire. He was the eldest of four siblings (two sisters and one brother). His father, William, was a caretaker at the local school, who made extra money by collecting horse manure from the street and selling it, presumably as fertiliser. His mother, Alice, worked in the kitchen of a boarding house. Although Bertie came from a very modest working class background, he was able to attend King Edward VII Grammar School in Lytham by obtaining a scholarship. There is no way his family could have afforded to send him to school without one.

Bertie did very well in school; the family still has his school report cards from 1910-12, and he performed well in every subject! After graduating from school, he joined The Oakfield Manufacturing Company as a salesman. Just three years later, at the age of 19, he would volunteer to fight in the First World War.

Bertie’s War:

1917: Following the war, Bertie never spoke of his war experiences with his family. All he would share with the family was that he was up to his waist in mud on his 21st birthday, and that he was gassed on two separate occasions. Thankfully, Bertie’s war records are relatively well-preserved, so we can get a clearer picture of his time in service.

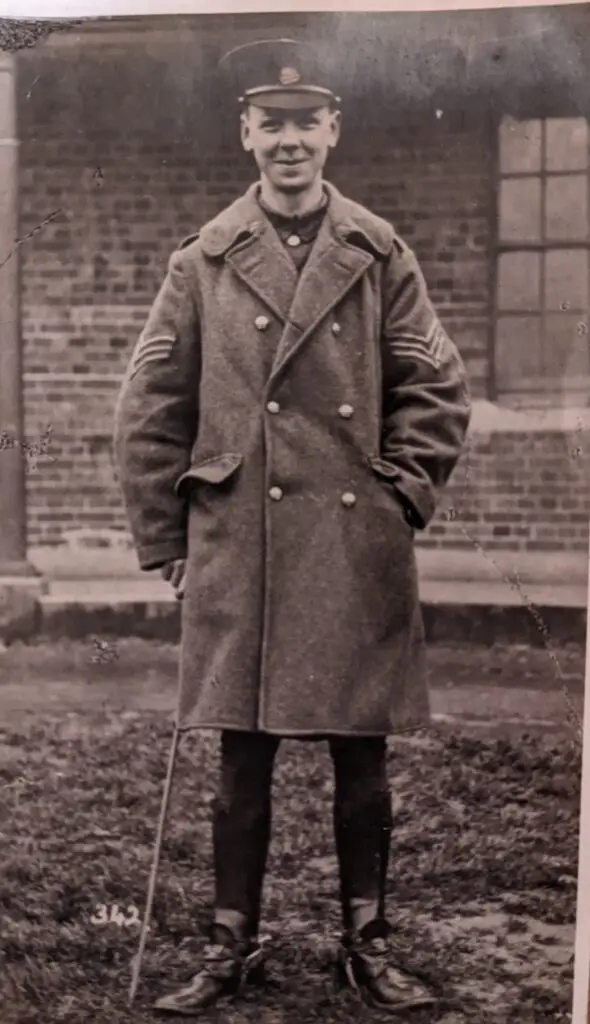

Bertie volunteered for the Armed Forces on 1 April 1915 and, after completing training, officially joined the British Expeditionary Forces on 17 June 1916. Bertie joined the Duke of Lancaster’s Own Yeomanry, which was predominantly a cavalry unit. We know that he loved horses, so this no doubt influenced his choice of unit. However, due to the conditions at the Western Front, cavalry units were becoming obsolete. The Duke of Lancaster’s Own Yeomanry were assigned to France in May 1917, and began training as infantry units, which eventually became the 12th (DLOY) Manchester Bn.

The 12th (DLOY) Manchester Bn. was sent to the frontline at Passchendaele on 9 November 1917, the day of Bertie’s 21st birthday. Passchendaele was notorious for its horrendous conditions; the fighting was fierce, and the land became so boggy and waterlogged that the only way to move around was by using narrow paths made out of wooden duckboards. Men who fell

from the narrow path often became stuck in the mud and drowned.

As the war had now been raging for three years, the German forces were now throwing everything they had at the Allied lines: artillery, gas, and warplanes, all of which Bertie experienced on his 21st birthday. As we can see from the day-by-day reports written by the commander of the 12th (DLOY) Manchester Bn. (all of which are available online), Bertie and

his friends in B Company came under heavy artillery fire and sustained many casualties on 9 November 1917. C Company was the worst hit: late in the evening of 9 November, German infantry stormed the C Company’s positions, capturing and killing many. On the left flank, while Bertie was waist deep in mud, 20 German planes strafed their positions with machine guns, shooting flares to mark targets for the artillery bombardment. The artillery rained down all night and continued for several days. Conditions were so bad that mud clogged up the British rifles and rendered them useless. The commander called up additional machine guns to account for the loss of rifle fire.

This bombardment continued for several days, until the Battalion was pulled out on 14 November. On the journey back from the frontline, the Battalion was shelled heavily by gas in the support lines, and warplanes fired at the narrow duckboards with machine guns and bombs. Once finally off the line, there were many reports of trenchfoot, as the men had spent so many days in the waterlogged mud. Through December and over Christmas, the 12th (DLOY) spent their time reinforcing British positions to prepare for a predicted German offensive.

1918:

Due to the heavy losses sustained by the 12th Manchester (DLOY) Bn. in November, the Battalion spent a lot of time off the front line, reinforcing British positions with barbed wire and helping artillery units. When preparing for the Spring Offensive, the 12th (DLOY)s were placed on the flanks, where it was considered less likely to sustain heavy enemy attacks. Predictions were wrong, and the German forces focused their attacks on the flanks.

The positions on the 12th (DLOY) were shelled with mustard gas and attacked by large German raids, which were driven off. Other sections of the line were unsuccessfully defended, which meant the 12th were ordered to retreat to Havrincourt and defend it. The German army mounted multiple attacks, which became so close quarters that many grenades were thrown between the two sides. The 12th repelled the attacks, and were later assisted by artillery, which inflicted huge casualties on the German attackers. The brutality of this combat cannot be under estimated.

Due to the ongoing offensive and breakthroughs elsewhere, the 12th (DLOY) Battalion engaged in a fighting retreat. The Battalion was continually ordered to fall back to new positions, defending each before falling back again. Needless to say, losses during this time were substantial.

From Bertie’s medical record, we can see that during the retreat on 26 March 1918, he was taken off the frontline, after suffering a gunshot wound and one other injury (sadly, illegible on his medical record). Bertie spent several months in hospital, before being transferred to the Labour Corps to help in a non-combat role. He remained in this role until the end of the war.

After the War:

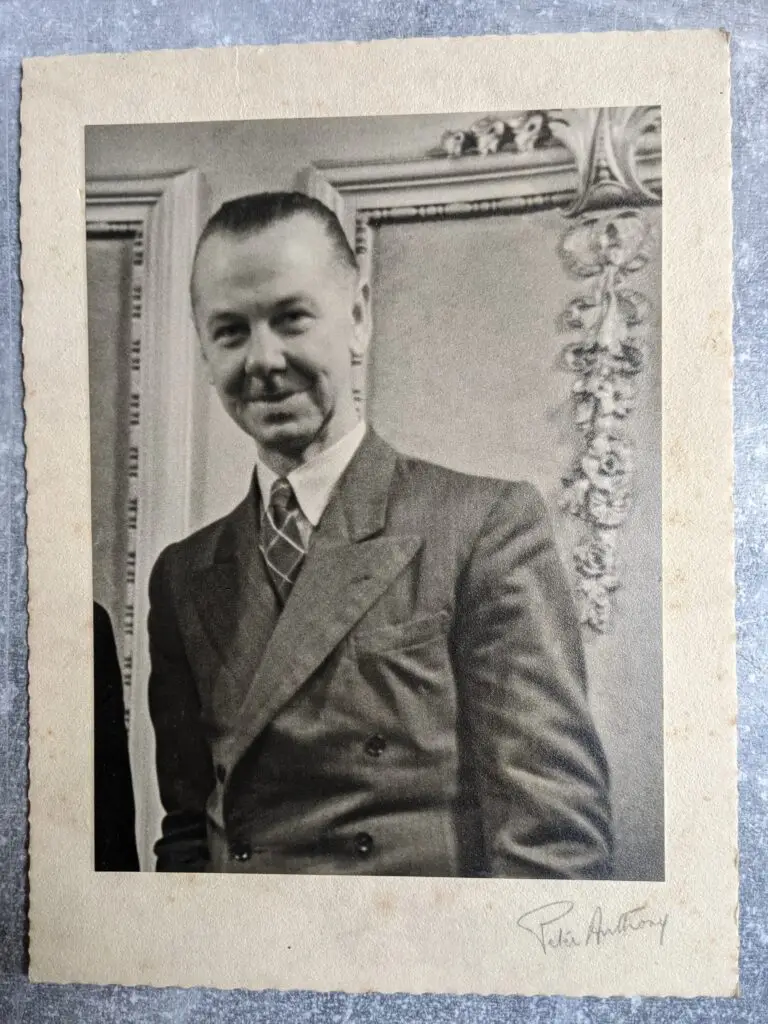

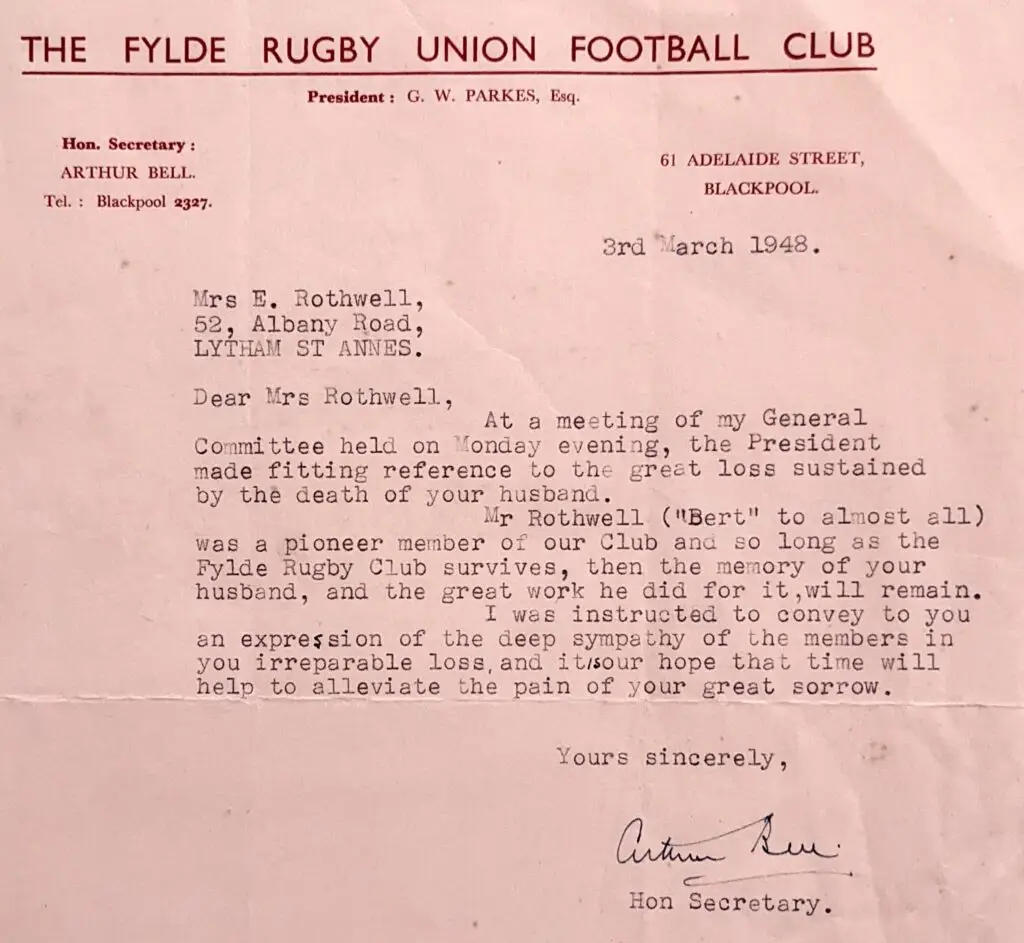

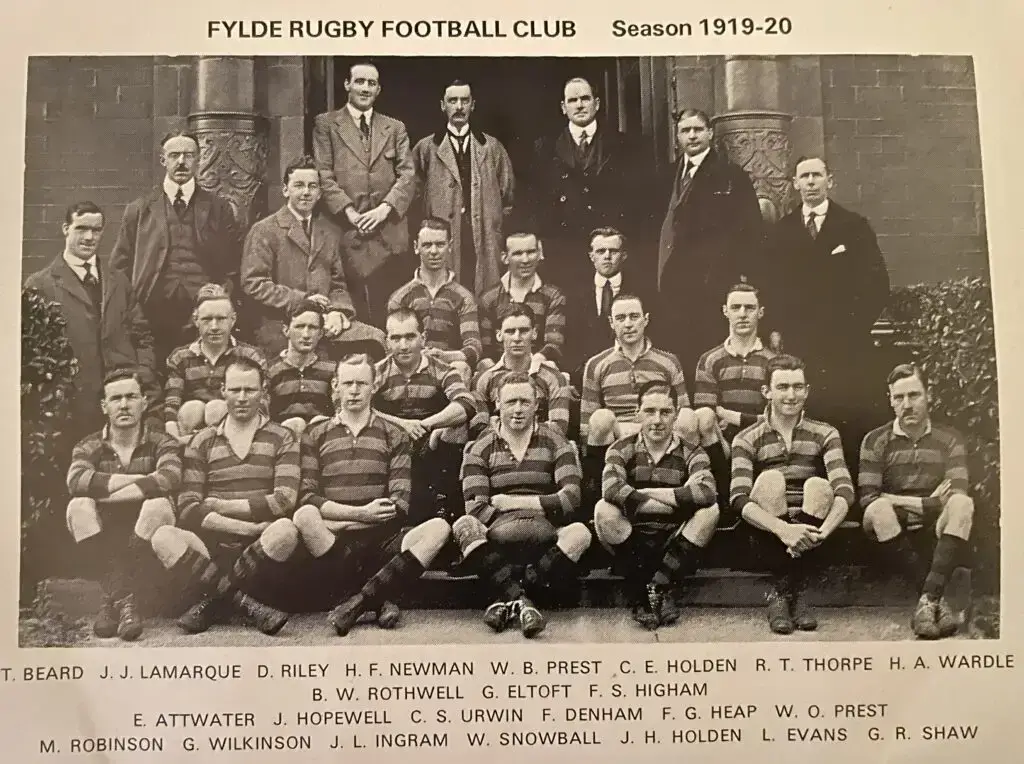

After the War, Bertie was involved in several unsuccessful businesses. Due to his crippling post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), at the time known as ‘shell shock’, he did not have the concentration or mental capacity to fully commit to the businesses. He did, however, have time to pursue one of his passions: rugby. Bertie was one of the founding members of Fylde RFC, appearing in all the teams between 1919-23. It is unknown how much of a role he played in the formation of the Club, but the letter Fylde RFC sent to his wife Elsie, upon his death, suggests that he was highly regarded within the Club.

In 1929, he married his wife Elsie, and in 1931 had a daughter, Jean. Bertie adored his daughter Jean, and helped her to learn piano, at which she was very talented.

In the 1930s, Bertie set up a slipper and shoe manufacturing business, Rothwall and Markus Ltd, with a German Jewish refugee called Markus.. From what we know, Markus was very patient with Bertie and sympathetic to his PTSD, and did most of the running of the business. Bertie tried to manage his PTSD by resorting to alcohol, to numb his distress. ‘Shell shock’ was not something which was openly discussed at that time.

On 19 February 1948, Bertie complained of pain in his stomach. Eventually, after the problem persisted, he was taken to hospital. Sadly, he was pronounced dead that evening from a perforated ulcer.

Bertie suffered throughout his life with PTSD and subsequent alcoholism. Those who knew Bertie said he would help anyone around him, and almost every condolence letter commented on his infectious smile, and what a happy man he seemed. Bertie did not die on the frontline in the trenches, but he was certainly a casualty of the Great War.